Prepared by: Munir Najjar

Lebanese from “Kasha” sellers to owners of huge shops and factories

The ancient migration began with farmers and then extended to men of thought and politics.

To study the history of Lebanese immigration, we must go back four thousand years in ancient history, the time when the Phoenicians, who were the “first Lebanese,” began their adventures across the seas, and who, according to some historians, reached the American continent in the middle of the twelfth century BC. Studies in this context have relied, in particular, on the Phoenician writings on the stones of Gavia and Paraíba in Brazil. As historians continued their investigations, they confirmed the presence of Arabs in Latin America in the seventh century AD when the ruler Ibn Barajil arrived from Marrakesh and Cordoba to the island of Alasor, and then achieved the feat of crossing the Atlantic Ocean in 705 AD, reaching the mouth of the Parnaíba River in the state of Piauí (currently), and moving along the shores, he reached an area called Infra dos Reis today.

This ruler mapped the coast and concluded it with the title “Brajil” and gave the mapmakers all the necessary explanations. In their follow-up research, historians verified the Arab and Lebanese presence in Latin America during the Spanish and Portuguese expansion in the twelfth and fourteenth centuries AD.

Arabs in Brazil

Historical documents speak of Arabs in the expedition of Pedro Álvares Cabral, during which he discovered Brazil in 1500. There are documents indicating that Portuguese sea captains, including Cabral, were Arabs. The maritime centers of Sagres, Palos (from where Christopher Columbus sailed) and Venice used Arab nautical charts, because the Arabs were excellent sailors who were proficient in astronomy. Hence the popular saying that “the Arabs were born in Brazil with its discovery.”

There are other documents dating back to the period of colonization of Brazil confirming that the Arabs came to it during the colonization period, coming from Portugal or from Africa. They were considered “friendly foreigners who helped the Portuguese colonize the overseas lands.” There are stories that say that the Arabs arrived in Brazil in 1547 accompanied by the governor, and began to settle and open shops.

The historian Adolfo Bezerra de Venezes narrates that a Lebanese named Antón Elias Lepes (whose Portuguese name was changed to Elias Antonio Lopes after he lived for a few years in Portugal), a merchant in Rio de Janeiro and a landowner in Praia, presented his house to the Portuguese King Don Juan VI, who came to Brazil from Portugal. Since the Lebanese’s house was one of the largest houses worthy of the king, he permanently transformed it into the Brazilian Imperial Palace. The place was then called “Paso de São Cristóvão”, where Don Pedro II was born. Today it is the home of the “Quinta da Boavista” Museum.

Between East and West

The great Lebanese and Arab migration to the New World began in the nineteenth century, for many reasons, some of which were related to the internal situation in the East and others to the situation in the West. In the East, the Ottoman Empire did not guarantee freedom or security. As for present-day Lebanon, at that time, it was divided into two regions: Mount Lebanon, which enjoyed self-administration under European protection, while the greater part of the plains in the Bekaa Valley and the coasts were under Turkish control. Persecutions multiplied, and the loss of freedom and security, as well as the lack of geographical scope due to the narrowness of the lands and the control of feudalism, did not provide much scope for the economy, which prompted many Lebanese to emigrate, so they headed across the sea in search of new lands, which marked the beginning of the mass migration in 1856 to the United States, which was practicing an immigration policy aimed at attracting immigrants to fill the void in its lands.

The civil war in Lebanon in 1860 led to an increase in fanaticism and led to the destruction of Lebanon and the fall of thousands of victims in horrific massacres, which increased the number of immigrants to Egypt first, which provided a good field for agricultural work, especially in the Alexandria region. Then these people started heading from Lebanon and Egypt towards Europe, Australia, Western Asia, Africa, the Pacific Islands and North America. This last destination was the great dream of the Lebanese who always said that they wanted to go to “America”.

It is worth noting that Lebanon went through a period after the rule of Mutasarrif Rustum Pasha that was characterized by the injustice of the feudal lords towards the peasants, especially in the Bekaa Valley. The Lebanese were forced to migrate en masse since the late nineteenth century in search of better living conditions in new countries.

Migration to Brazil was distinguished by the fact that it consisted not only of farmers but also of members of the political and cultural elite. One of the goals of migration was to ensure a free life in exile and then return to live a better life in the homeland.

The first Lebanese immigrant

There are disagreements about the first Lebanese to immigrate to Brazil, but many investigations indicate that the citizen Youssef Moussa, born in Miziara in northern Lebanon, who arrived in Brazil in 1880, was the first Lebanese to leave Lebanon heading directly to Brazil, unlike those who first went to Egypt and Europe and then headed to Brazil. At the same time, the first group of immigrants from the town of Sultan Yacoub in the Bekaa Valley arrived in Brazil, followed by other groups, and the story of Lebanese immigration to Brazil began.

The Lebanese immigrants, whether farmers or intellectuals, arrived in Brazil, especially through the ports of Santos and Rio de Janeiro, empty-handed, so they had to start from where they arrived… However, the spirit of courage they possessed pushed them to search for a living in freedom in three Brazilian presidential regions: the northern region where rubber was produced, the central region where the mines were, and the south where coffee was produced. There they struggled for better days and became, alongside the Brazilians, Italians and Germans, discoverers and colonizers of these regions. The Lebanese in particular embarked on itinerant trade, selling junk. They carried boxes in which they displayed combs, mirrors, perfumes, etc. Since they knew that the Brazilian people were religious, they displayed things they had brought from their country and that were said at the time to be “holy” because they came from the Holy Land, such as pictures of saints, relics and bottles filled with “Jordan River water.” They sold all of that in the streets, villages and shops, which is why they were initially called “Cashiros” and in Arabic “People of the Kasha” (People of the Box). After a while, they increased the quantities of goods and traveled between neighboring cities, becoming “suitcase merchants.” The Brazilian diplomat and historian Dolgo Menazes said about them that the suitcase merchant was related by lineage to the first explorers and conquerors (the Bandeirantes). In fact, these kosha merchants played a historical role in the development of the interior regions of Brazil, as they reached places where mail did not reach at that time and brought to those places the events and news of the big cities, helping to strengthen the connection between the countryside, the sugarcanes and the cities.

Starting from the “kosha” that they carried on their backs, they opened small shops that eventually turned into large commercial stores. Then, when they felt economic stability and social integration, they began to deal with matters of culture, science and politics and established clubs, associations, schools, orphanages, hospitals and newspapers. The first newspaper in Brazil in the Arabic language was published in the city of Campinas in 1895 by Salim Balish, a Lebanese who was originally from Zahle, which was called “Al-Faihaa”, thus demonstrating that the idea of staying permanently in Brazil, the land that embraced them and welcomed them with open arms, was possible.

Brazilian stone of Phoenician origin

Some archaeologists and historians say that the Phoenicians arrived in the Americas and in Brazil before Columbus, leaving behind many stone inscriptions. Among them is the one engraved on the “Gafia Stone” in Rio de Janeiro, which constitutes the first document on the subject. The Brazilian historian Bernardo concluded that the Gafia Stone is Phoenician and that the inscriptions were engraved during the reign of Gethsabaal, King of Tyre (Lebanon) between 887 and 856 BC or during the reign of Badizer between 856 and 850 BC.

After some time, the Belgian professor Albert van den Branden studied the stone and confirmed that the writing was in the Phoenician language, but he did not agree with Bernardo’s conclusions and dated the inscriptions back to between the second century BC and the first century AD.

Another Phoenician inscription in Brazil is that found at Pouso Alto, which Dr. S. H. Gordon translated as follows: “We are the sons of Canaan, from Sidon, the city of the king. We were carried by trade to this distant shore in a mountainous land. We sacrificed a young man on the altar of the gods and goddesses in the 19th year of our mighty king Ahiram. We set sail from Ezion-geber in the Red Sea and traveled in ten ships. We remained at sea together for two years through those lands of Ham (Africa), but we were separated from our companions by a storm. Thus we arrived here, 12 men and 3 women. We arrived at a new shore, which I, the commander, have placed under my supervision. But we asked the gods and goddesses to intervene in our favor.”

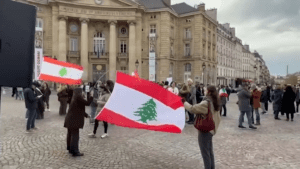

Between immigration, expatriation and diaspora,

three of the most prominent expressions used to define the “Lebanese immigrant” according to the historical stages that this migration has gone through, but there is no official consensus on the unity of meaning for these terms, which differ between the “dictionaries” of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Expatriates, which are originally concerned with this topic.

Ambassador Fouad Al-Turk considers that the expatriate is the Lebanese who was born in Lebanon and immigrated from it, and in his view, expatriates constitute a small percentage of the expatriates. He sees the meaning of the expatriates as more comprehensive and general, as it includes these expatriates and their descendants together, and the phrase “expatriates abroad” includes expatriates and the rising generations after them.

The first Minister of Expatriates, Reda Wahid, believes that the first waves of immigration gave birth to what is called the descendants who left Lebanon with the hope of returning to it one day, and that the immigration after World War II witnessed a qualitative shift in classification and identity, becoming a spread. Is the Lebanese who immigrated twenty years ago and is in a country where he does not want to settle classified in this category? Until now, we have not found a radical definition to follow in defining the Lebanese expatriate.

Al-Hadith newspaper indicates that Ambassador Fouad Al-Turk was the first to use the term spread to describe immigrants, and he also suggested naming the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Lebanese Diaspora in 1983.

President Elias Hrawi, during whose term the “Ministry of Expatriates” was established, distinguished precisely between the meanings of expatriates and those spread. In his opinion, it was closer to the dictionary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs than to the dictionary of the Ministry of Expatriates. In his view, the expatriate is one thing and the Lebanese spread across the world is another, as the first category has a closer relationship with their country than those who immigrated and were called expatriates since the days of the Ottoman era. He demanded changing this name so that there would not remain multiple characteristics for those who spread out, and this quantitative spread later produced a qualitative alienation and called for expatriate relations, especially with those who began the journey of spreading out since 1958 because these represent the real alienation.

Thus, the concept of the Lebanese immigrant, according to Reda Wahid, historically progresses from descendant to diaspora to reach expatriate. While this concept, according to Fouad Al-Turk, progresses from expatriate to descendant to include the expression of diaspora for all of them, and he says: “The ideal word for the expatriate and his children and grandchildren is the Lebanese diaspora.”

The apparent disagreement in the meaning of the three main data between the minister and the ambassador was not only a disagreement in form, but rather extended to an actual problem in essence that prevented the two ministries from reaching an agreement on a single, unified meaning for these expressions. Ambassador Elysee Alam wonders whether the expatriate is the descendant of the third generation (3éme génération), whether he is the Lebanese who immigrated twenty years ago and is in a country where he does not want to settle.. So far we have not found a final, radical definition…

References:

- The book of the Brazilian historian Bernardo de Azevedo da Silva Ramo, entitled “Writings in Prehistoric America”.

- The book of Roberto Khattab: “Brazil and Lebanon… A Friendship that Defies Distance”.

- Documents found in the Marshal Rondoff Museum.

- The book of Qaysar Maalouf, “Memory of the Immigrant”.

- The book of Dr. Jihad Nasri Al-Aql.